Introduction

Vertigo is a symptom of illusory movement, especially rotatory. It is very common symptom that most people have experienced at some point in their lives, for example after turning around rapidly several times. Vertigo may also be described as a sense of swaying or tilting or may be perceived as a sense of self motion or motion of the environment. It is important to note that vertigo itself is a symptom rather than a diagnosis. It can arise from abnormalities in both the peripheral and central nervous system. Vertigo is a subtype of the more general symptom of dizziness. A subjective sense of dizziness may also include a sense of faintness due to low blood pressure, poor balance, or otherwise ill-defined lightheadedness. The diagnostic evaluation of vertigo focuses on differentiating more benign peripheral sources of vertigo from more serious and disabling central causes. Interestingly some of the subjectively most severe vertigo is symptomatic of benign causes and vice versa. Hence the need for medical, neurological or ENT evaluation.

Symptoms

Vertigo itself is the predominant symptom of vestibular dysfunction. The vestibular system peripheral receptors are in the inner ear in the temporal bone adjacent to the cochlea that perceives auditory stimuli and enables hearing. The information from these structures travels together to the brainstem part of the central nervous system through the eighth cranial nerve which is why vertigo and hearing problems may occur together. As noted above, vertigo can be described as a sense of spinning or swaying but is often difficult to describe in such specific terms. Dizziness, imbalance, and disorientation may eventually prove to be associated with vestibular dysfunction. Vertigo may also be associated with a sense of nausea as well as vomiting, particularly when the symptoms are acute in onset. Severe nausea and vomiting are more commonly associated with vertigo that is peripheral in origin rather than central. Patients with vertigo may also have problems with maintenance of posture and balance. Vertigo that is central in origin often impairs gait and posture to a greater extent than severe spinning vertigo that is peripheral in origin.

Diagnosis

A complete medical history, including a comprehensive review of medications, and a physical exam can help determine the origin of vertigo or dizziness. Your doctor may perform the Dix-Hallpike maneuver using head position changes to reproduce vertigo in the office and elicit nystagmus (jerking eye movements), to more precisely localize the source of the symptoms. Hearing tests may be advised. It is important to differentiate dizziness/disequilibrium which is constant and chronic from a more episodic sense of spinning vertigo as the former is generally not associated with more benign peripheral vestibular dysfunction.

Recurrent vertigo lasting under a minute triggered by head movement, especially getting up in the morning, turning over in bed or lying down at night is typically associated with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). At the risk of oversimplification, this is due to crystals in the inner ear that have migrated to a site where they abnormally stimulate the receptors in the inner ear with head movement.

Episodes of vertigo lasting several minutes to hours may be associated with migraine symptoms or disruption in blood flow to the brainstem.

Recurrent episodes of vertigo associated with Ménière's disease/endolymphatic hydrops may also last for several hours and can be associated with hearing changes including hearing loss, tinnitus (spontaneous noise in the ear or head) and ear fullness.

Prolonged, severe episodes of vertigo that occur with vestibular neuritis may last for up to several days or weeks. Vestibular neuritis is a benign syndrome, but a similar set of symptoms may also suggest multiple sclerosis or a stroke affecting the brainstem or cerebellum, making consultation with a medical professional essential.

Head trauma may also produce vertigo through a variety of mechanisms.

A history of recent hyperextension or manipulation of the neck with trauma that may be mild (even rarely as a complication of chiropractic treatment) could be associated with vertebral artery dissection with disruption of blood flow to the brainstem. Focal neck pain and vertigo after such manipulation may suggest vertebral artery dissection. Acute vertigo due to a vertebrobasilar stroke is almost always accompanied by other brainstem localizing signs such as double vision, slurred speech, difficulty swallowing, weakness, or numbness. The presence of any of these symptoms or severe new onset headache in association with acute onset vertigo should prompt an urgent evaluation in the emergency department for a stroke including hemorrhage.

An antecedent viral infection followed by vertigo is suggestive of acute vestibular neuritis which is believed to be associated with viral or post viral inflammation of the cranial nerves VIII.

Summarized below are a number of causes of vertigo divided into central and peripheral causes (distinguishing features in parentheses):

Peripheral:

- Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (recurrent, brief episodes of vertigo lasting for a few seconds triggered by predictable head movements or positional changes)

- Vestibular neuritis (acute onset vertigo, single episode, lasting days following a viral syndrome, tendency to fall towards the affected side)

- Ménière disease (recurrent episodes lasting minutes to hours associated with a sense of fullness in the ear, ringing and hearing loss)

- Perilymphatic fistula (history of head injury, episodic vertigo precipitated by sneezing, heavy lifting, coughing or straining)

- Semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome (brief episodes of vertigo is provoked by coughing, sneezing, or exposure to loud noise)

- Acoustic neuroma (gradual onset of typically mild disequilibrium/unsteadiness with associated unilateral hearing loss)

Central:

- Vestibular migraine (recurrent episodes of vertigo lasting minutes to hours, history of migraine and other migraine symptoms such as nausea and light sensitivity). Headache may not be present.

- Brainstem stroke (sudden onset, persistent symptoms for days to weeks associated with other signs of brainstem dysfunction including slurred speech, double vision, weakness, and numbness)

- Cerebellar stroke/hemorrhage (sudden onset, persistent symptoms for days to weeks, unsteady gait, incoordination of extremities, headache)

- Multiple sclerosis (subacute onset of vertigo over hours, resolution over days to weeks, history of other neurologic episodes in past)

- Disembarkment syndrome or mal de debarquement (onset of disequilibrium rather than rotational vertigo after exposure to passive motion such as travelling by boat or plane – often described as feeling as if still on a moving boat after returning to land)

Laboratory tests may be pursued that can further determine the etiologies of dizziness. Videonystagmography (VNG) can be performed to evaluate the balance function of the inner ear. Imaging studies such as CAT scan or MRI scan of the head can further study the anatomy of the brain, hearing and balance nerves, and sinuses. A transcranial Doppler scan (TCD) and carotid duplex ultrasound may also be requested to evaluate the blood supply to the brain.

Treatment

Treatment of the underlying disease, where possible, may diminish the symptoms of vertigo in the context of most of the condition as noted above.

- Symptomatic treatment may also include medications:

- Antihistamines (meclizine, diphenhydramine, Dramamine)

- Benzodiazepines (diazepam, lorazepam)

Medications may help alleviate the acute symptoms of vertigo but do not necessarily address the underlying source of the symptoms and are limited by sedative side effects. These medications are used for the shortest duration possible to avoid compromising long-term adaptation to vestibular dysfunction by the brain, which occurs gradually over time with improvement in, or resolution of, the acute symptoms.

Vestibular rehabilitation (physical therapy) may also be recommended and promotes recovery and individuals that have permanent dysfunction in the peripheral vestibular system and may also be beneficial in patients with central sources of vertigo.

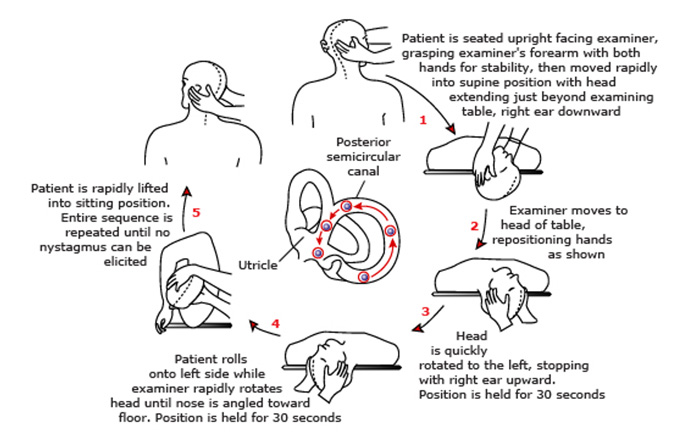

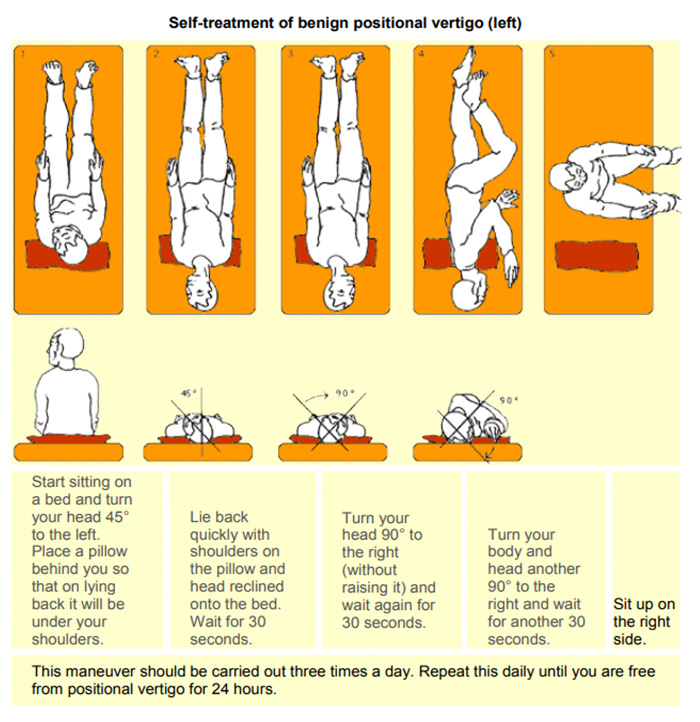

BPPV in particular is effectively treated in most cases using particle repositioning maneuvers such as the Epley maneuver illustrated below:

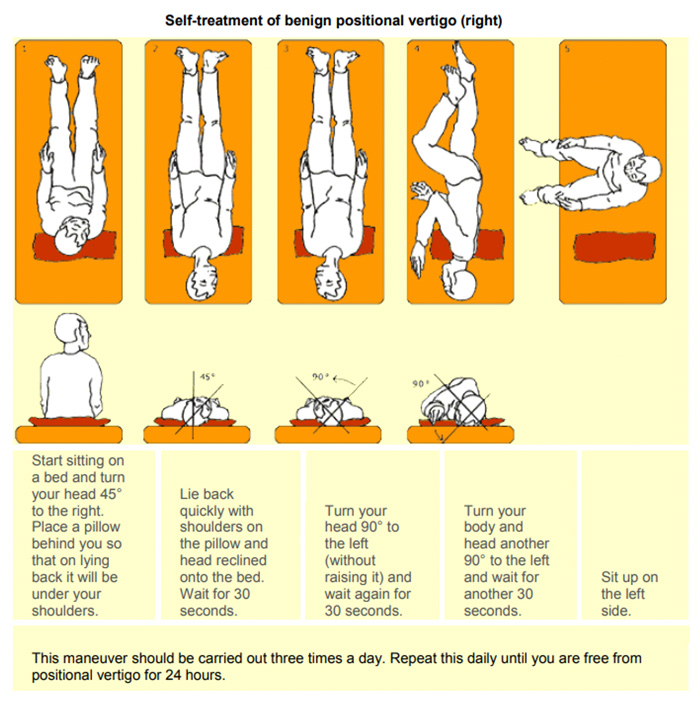

If the diagnosis and localization of BPPV has been established by your doctor and other causes ruled out, a DIY home modification Epley maneuver is nicely illustrated in many YouTube videos and in the document below:

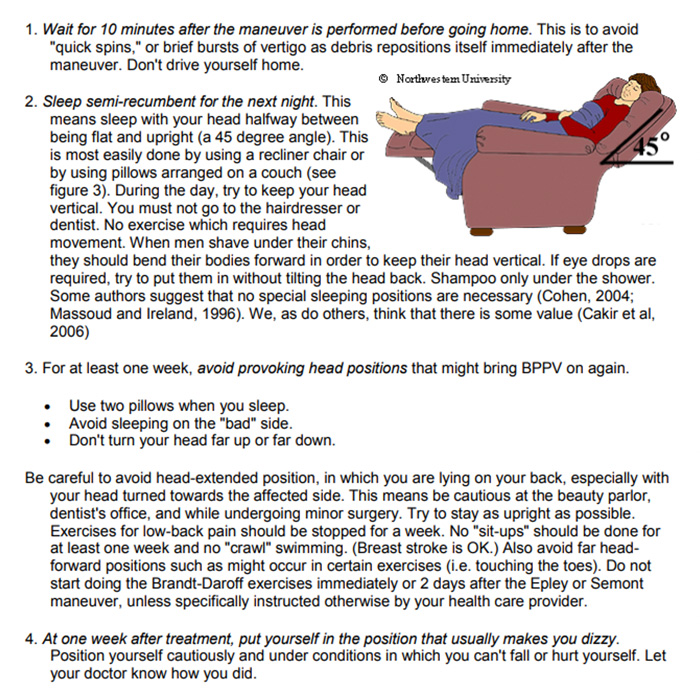

Instructions for patients after treatments

(Epley or Sermnont maneuvers)